(My apologies to Richard III)

Earlier posts have opined on the rise of China’s higher education infrastructure and its increase in research article production in the mid-2010’s, exponential growth that surpassed the volume of US scientific publications.

A report from STINT, the Stiftelsen för internationalisering av högre utbildning och forskning in Sweden

takes advantage of Scopus, a database tracking about 34,000 peer-reviewed journals in life sciences, social sciences, physical sciences, and health sciences. The report studies the period 1980-2021.

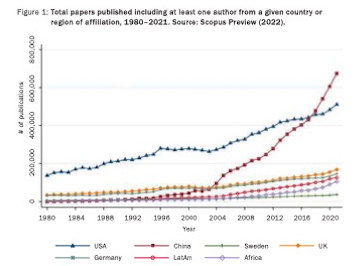

First, the report again documented the exponential growth of scholarly publications from China, as shown below in the figure labeled Figure 1. This phenomenon has been the focus of much discussion probing the causes of this change (e.g., incentives to publish), further analysis on the impact of papers (e.g., citation rates), and implications for national competition.

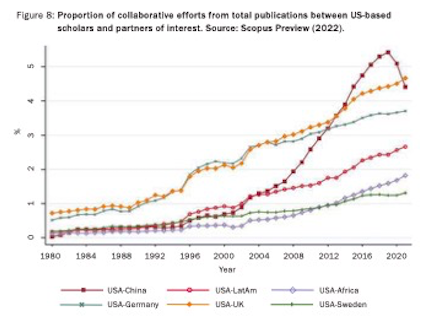

Second, during these years, an important additional trend was developing – greater collaboration among scholars in different countries.

The figure below (labeled Figure 8) from the STINT report, shows the percentage of collaborative publications between US research and colleagues in other countries. The y-axis is the percentage of all papers published by scholars in two given countries that were collaborative across two pairs of country’s scholars.

The first conclusion of the trends is that the tendency of US scientists to collaborate with colleagues in other counties increases during this time period, especially from 1998 onward. There are many changes that took place in this period, including the ubiquitous use of the internet and greater nation-state support of international collaboration.

Notice, however, the sharp decline in the last three years of the USA-China percentages.

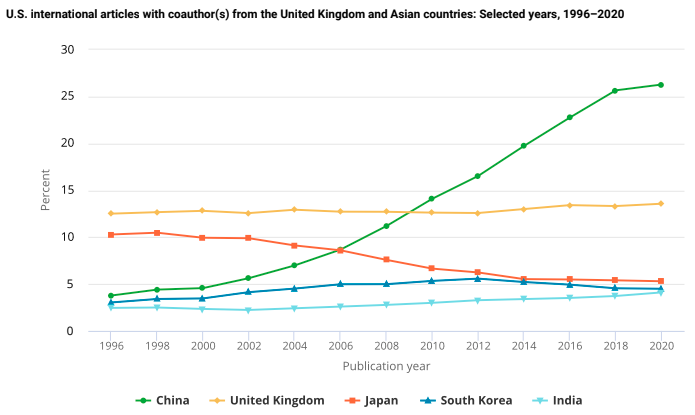

Another report, from the US National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) uses data from the same Scopus source. Figure PBS-5, from that report, plots co-authored papers between US scholars and those from other countries. The green line shows the same dramatic increase in US-China collaborative publications as the STINT data, but no dramatic decline over the most recent years that was evident in Figure 8 above.

Why do these two charts imply different trends?

First, the number of scholarly publications is increasing rapidly among Chinese scholars, quite sharp and exponential growth, especially since 2010 or so. Growth in the number of articles by US researchers is also increasing, but at a much lower rate of increase over the years.

The STINT Figure 8 divides the number of co-authored US-Chinese publications by the sum of total publications by US scholars and the total by Chinese scholars. The NCSES Figure PBS-5 divides the number of co-authored publications only by the total number of US authored publications.

When the number of collaborations are divided by the number of total US publications, the percentage of US-scholar articles co-authored with Chinese scholars is not declining. However, when the number of collaborations are divided by the total of US and Chinese scholar articles, the percentages are rapidly declining. In other words, Chinese co-authors are a larger proportion of US-scholars’ work. But US co-authors are a smaller proportion of Chinese scholars work. (Further STINT work shows this clearly.).

By the way, there is some indication that Chinese-European collaboration is also weakening. The STINT report cites new proposed laws in some European countries restricting such collaborations.

Denominators make a difference in conclusions about patterns. In this little example, the country currently exhibiting the largest global research product, China, is doing so with smaller percentages of work collaborative with US scholars. From the perspective of the US scientific product, the percentage of collaborations with Chinese scholars has not declined. But scholarly collaborations have not increased proportionately among US scholars to accompany the rapid growth of Chinese scholarship. Chinese scholars’ product seems less dependent on the US than was true in earlier years.

The phrase “A denominator, a denominator, my conclusion for a denominator!” seems to echo a poetic or rhythmic expression. It could suggest a focus on the importance of a common factor or shared foundation in drawing conclusions. The repetition emphasizes the significance of this denominator in reaching a resolution or decision. It carries a sense of urgency and importance, perhaps indicating the critical role that finding common ground plays in forming a conclusive understanding or agreement.

Apples & Oranges: digging deeper, how much of each country’s research is fruitful in terms of producing meaningful insights versus producing meaningless papers (quality versus quantity)?

Very interesting, thank you. Regrettably I have not yet had the time read the complete analysis and may have missed some points, in which case my apologies, but one thought is that there are of course always complexities and problems using publications to measure research collaboration or scholarship. Some that might be relevant here:

– China has different research priorities, most of those in fast growing topics.

– Being a communist country, it may be the case that their scholars may not be able to choose areas of study or with whom to collaborate as freely as those in the US and Europe.

– Regrettably, fewer US and European scholars can read and write Chinese vs Chinese scholars that can read and write English, in part because many Chinese scholars have been or currently are being trained in US and European Universities. As one consequence, it is usually easier for a Chinese scholar to collaborate on a publication written in English than it is for an English speaker to collaborate on an article that might be written in Chinese.

– A co author is not necessarily the senior author that led the study.

– US and European scholars tend to share co authorship differently. As a trivial example, at least in basic science, as resources have become tighter, many tasks have been “farmed out” to lower cost options … e.g. huge numbers of antibodies, candidate drugs, and other reagents more expensive to make in the US or Europe are now made in China due to cost saving necessity and if those molecules turn out to be important in a US or European study, many US and European scientists share co authorship with those that made them. The converse situation typically doesn’t hold. The point being that some of the co authorship trend is perhaps a simple consequence of economic and funding rate trends.

– Hopefully co authors are segregated into PIs vs students vs post docs in this study, if not, there are differences in traditions related to including the latter two as co authors.

Best

Paul

also perhaps a part of the ongoing discussion:

https://www.bmj.com/content/379/bmj-2022-071517#:~:text=Retracted%20paper%20mill%20papers%20most,those%20that%20are%20not%20detected.

Best

PD Roepe