Prior posts have discussed how the American public evaluates higher education; you can see last year’s commentary here. These posts presented the results of various surveys conducted either by the Pew Research Center or the Gallup Organization. The past few months have given us updates for this year.

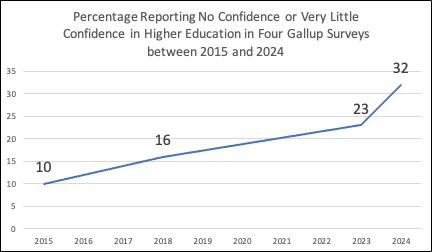

For example, the surveys have asked the question, “Now I am going to read you a list of institutions in American society. Please tell me how much confidence you, yourself, have in each one — a great deal, quite a lot, some or very little?” One institution is labeled “higher education.”

As presented in the chart, these four surveys show growing lack of confidence in higher education over a relatively short period of time. In one year, there is a jump from 23% to 32% claiming no confidence or very little confidence. In 2024, as in earlier years, both Republicans and Independents tend to report they have “no confidence” or “very little” confidence in higher education, relative to those who self-report as Democrats. Although this year’s report doesn’t probe the reasons, earlier surveys show reasons for lack of confidence among Republicans is much more related to perceptions that “colleges are pushing liberal political agendas on students.” On the other hand, the lack of confidence among Democrats seems related to concerns about the cost of higher education.

Now, having seen the statistics showing lack of confidence in higher education, it’s important to note that the vast majority of institutions (e.g., large tech firms, the Supreme Court, K-12 education) also show declines in trust over the last few years. Higher education is not alone.

But the skepticism about higher education expressed in this question doesn’t seem to match answers to other questions. For example, when asked about, relative to 20 years ago, how important it is for people to have a 2 or 4 year degree in order to have a successful career, there is little change between 2021 and 2023. About 40% of respondents report that it’s more important now than 20 years ago. So, the perceived value of higher education to one’s individual career shows little change over time, not following the growing lack of confidence in the institution.

What about behavioral intentions? The surveys asked those not currently enrolled in a program whether they were considering enrolling in a program, the percentage is increasing over the 2021-2023 period, from 44% in 2021 to 59% in 2023. When asked about one’s own feelings of pursuit of higher education, very different findings emerge than questions about confidence in the institution. (The top reasons for higher education aspirations is the capturing of more attractive jobs and professional career advancement.)

What are reasons that are cited as impediments to the desired enrollment? The challenge of paying the costs of the education looms large; the demands of child care are mentioned; and concerns about stress and mental health are relevant for many. (This latter impediment appears more prominent this year.) Further, some report that their current job market does not require higher education certification, reducing the attraction of formal schooling. (It’s relevant to note that several states have recently removed bachelor’s degree requirements from their state jobs.)

So in short, relative to prior years, this year’s round of surveys show increasing loss of confidence, but, at the same time, increasing desire to seek out higher education. The impediments to enrollment in higher education show a new prominence of stress and mental health concerns, but a repeat of the concerns about the costs of higher education. Our work continues.