Amateur genealogists around the world, who have ancestor connections in the United States, have been reveling in data in the last few days. After 72 years, images of the forms filled out in the US decennial census are released to the public. (There seems to be alternative stories about how the 72 year figure was chosen – some say it was a function of life expectancy at the time the decision was made.) Every year that ends in 2 brings a new release of a decennial census record.

My memory of this moment in 2012 was that there were hundreds of thousands of genealogists ready to access the electronic files for the 1940 census when the National Archivist, David Ferriero, announced the release. Within a relatively short period of time, electronic searches for names was facilitated by a unique private-public partnership. Private firms and individuals partnered to type in the 132 million names from all the census forms to permit name-based searches.

The 1950 census was just recently released for public inspection. Going to https://1950census.archives.gov/ allows anyone in the world to search for census records for people who were alive (and enumerated) in 1950 US.

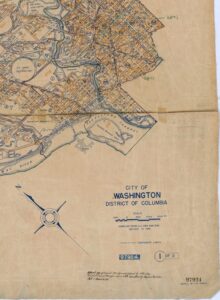

For novices, they have to learn a bit about the protocol of the data collection of censuses at the time (each decade is a bit different). For the 1950 census, thousands and thousands of temporary enumerators were hired to conduct face-to-face interviews at every structure that contain a household. The workload of an enumerator was heavily dependent on the nature of their assignment area. In rural areas, the enumerator might drive for miles between households, covering large territory. In urban areas, they might have a series of blocks, or even a small number of apartment buildings, depending on residential density. The basic building block of a workload was an enumeration district (ED), some, huge geographies; others, small. The entire US of 1950 was mapped into enumeration districts, the digitized maps of which are visible on https://1950census.archives.gov/, many of which are browned from aging and some of which are difficult to read, like the one below, showing the Georgetown campus area.

The map shows that the blocks around the university were in ED 1-537 in 1950.

So one of the first jobs is to determine where one’s ancestors were living around April 1, 1950. Starting with a city or county is good. It’s a beginning but only that. Careful inspection is often needed boing back and forth between ED maps and a current map of the area of interest. Cities have grown spatially since 1950. Next a street name is helpful. But streets have changed over time. Sometimes, despite all efforts, multiple EDs may be candidates. Eventually, choosing the EDs to inspect is made.

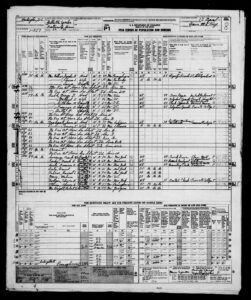

Next, for every ED, there is a set of pages listing persons. So, the search begins for the names of your relatives. In a small number of states (thus far) new machine learning algorithms have “read” the handwritten scripts and given hints at possible names, which can be searched. Most others require reading of lists of persons written in script by enumerators, address by address, person by person. The less information one knows about the location of the residence, the more searching that results.

The image below is a print of a listing of a block near the Georgetown campus, showing a fraternity house at 3401 Prospect.

So over the coming weeks, millions of persons will be reading line after line of these listings, searching for families they are interested in tracking down. When they hit their target, they’ll learn the reported household composition, relationships, race, ages, marital status, place of birth, employment status, hours of work last week, occupation, and industry of occupation.

Some will fill in gaps in their family history. They’ll be some surprises. Some joys. Some sorrows. For some, a family tree with new branches. It will be a ten year wait for the 1960 census release.

I’m curious. As a Cuban immigrant who landed here as a refugee in November 1960, I eagerly await the next census – I perhaps will finally find out where distant relatives landed in the U.S. and ultimately where they settled. I lost all tract of second and third cousins because not all parents who bonded the families made it over, and now many have long died. But, I do have a question: I just do not recall anyone from the government (census?) ever visiting our humble efficiency and asking us how many people lived there? The number varied from four to seven (sometimes the people who stayed with us were not direct relatives, but in the Cuban way if you grandparents knew each other you were sort of cousins, and hence they stayed until they got their own efficiency.) Consequently, how did the census keep tract of these immigrants in those days absent of interviews? I have to suspect that these historical records are mere approximations and that many immigrants will have no better information about their past histories than the family tales.

Thank you in advance for your thoughts.