Friday, March 1, 2024, is designated as Employee Appreciation day.

Of course, if employees are appreciated only one day of the year, there is something terribly wrong in the work environment. However, forcing a moment to encourage reflection on employee support is meritorious, and a designated day helps that.

Here at Georgetown we have a large variety of employees. Some of them work in countries or U.S. states far away from Washington, D.C. Some work remote from the campus, in workgroups that gather on Zoom most of the time but come to campus once a month or so for group face-to-face meetings. At the other extreme, we have colleagues who arrive every day and spend eight or more hours contributing to the university.

Unfortunately, the slow adaptation to a post-pandemic work environment has complicated communication among employees of the university. As I walk the halls of some academic departments, for example, most faculty doors are closed, but staffs are at their stations by and large, greeting students, visitors, delivery workers, etc.

It’s harder to deliver an impromptu compliment to a co-worker with the prevalence of Zoom/email/chat. Most Zooms are not spontaneous; text is a little better, but probably too task-oriented for effective affective communication. There’s no coffee maker to permit a chance meeting of members of the same unit. It was a lot easier just passing a colleague in the hall or exiting side by side from a meeting.

In universities, everyone is an employee of the institution. In that sense, each of us has some day-to-day opportunity to appreciate our colleagues. Employee recognition is a duty of a work culture not only a management design.

Employees of Georgetown spend many hours a week working to fulfill a proud mission of the university. All of them are asked to be flexible to the dynamic nature of a university, to be empathetic to those they serve directly, to take the initiative to fulfill the mission, to show integrity, to be honest, and to support the culture of people for others so key to Georgetown. Appreciation paid for these attributes is highly deserved. We’re fortunate to have mission working for an end much larger than our own job. Doing this in our work groups is a meaningful part of many of our lives.

So, what’s the point of this? This Friday is a great reminder that supervisors need both to facilitate the productivity of their teams, but also foster a culture of appreciation of all those in their unit for their contributions to the whole. Supervisors need to link the larger mission of the university to the contributions of every single staff member. So, Friday is a good moment to thank them for those contributions. Supervisors have a special role.

But it’s also an opportunity for everyone. We can thank our peers in the university for what they do for the mission and their support of our own work. We can thank those in similar positions as ours. We can take just a moment to note that their work helps us in ours. So, in a sense, all of us have a role in building a culture of appreciation of all employees. Friday might be a day to communicate that in a simple but sincere way.

Address

ICC 650

Box 571014

37th & O St, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20057

Contact

Phone: (202) 687.6400

Email: provost@georgetown.edu

Demographic differences in Social Media Usage

Posted onRecently, there was an interesting report on US adults use of various internet platforms, based on national survey results.

We have all read the boasts about how many users exist on different platforms, but we are also aware that many of the “users” are bots that are unconnected to any individual. Using surveys to have real humans report their own behavior is less sensitive to bots.

The survey asked the question: “Please indicate whether or not you ever use the following websites or apps.” The order of penetration is not too surprising: YouTube (83% of the respondents report use), Facebook (68%), Instagram (47%), Pinterest (35%), TikTok (33%), LinkedIn (30%), WhatsApp (29%), Snapchat (27%), Twitter/X (22%), and Reddit (22%).

While each of us has preconceptions of what this ordering might be, the demographic breakdown of users is more interesting.

First, despite the political polarization of internet-related activities, the differences between the political party affiliates is relatively small across the different platforms, in general. For example, YouTube, Facebook and Twitter don’t show large differences in use between party identifications.

There is, however, a platform with noticeable differences between the two parties’ usage. Instagram is used by 43% of Republicans/Lean Republican but 53% of Democrats/Lean Democrat. Some speculation about this is the skew of Democrats to younger persons, with affinity to Instagram influencers. There is some evidence of Instagram use for issues like climate change, racial disparities, and other issues. In short, the platform appears to be used for influence regarding traditional progressive causes. Hence, the contrast between the two political parties.

Over all the platforms, the most ubiquitous single predictor of use is age of the respondent. The 18-29 year-old respondents report very different behaviors than older respondents. Indeed, as above, Instagram is one of the platforms that shows large age differences, with 78% of the 18-29 year old’s using the platform but only 35% of those 50-64 years old (only 15% of those 65 and older). Age differences are also notable in the Facebook usage statistics. For that platform, the usage rates are highest in the two middle age groups, and lowest in the youngest and oldest age groups.

Another interesting finding concerns LinkedIn, where education and income are strong predictors. Both respondents earning over $100,000 per year and those with a College or more education report a 53% usage rate. The age distribution of usage reflects the popularity of LinkedIn among those in prime earning years; those over 65 years of age have the lowest usage. Usage patterns of LinkedIn look like those of no other platform.

Two other platforms have different demographic patterns. Proportionately more Hispanic respondents (54%) use WhatsApp than other race/ethnicity groups (e.g., White use is 30%). Why might this be? It’s interesting to note that in Central and South America WhatsApp spread as one of the first instant messaging platforms that was free of charge (providers in those countries tended to charge per message on cellular services). Its popularity there remains high. This apparently affected Hispanic use in the United States as well.

The Snapchat usage is interesting as well. Snapchat is a messaging platform whose content, once viewed by a recipient, disappears from subsequent views. It has a set of game features and whimsical video editing tools with entertainment in mind. Further, it seems well designed for mobile-only usage. Among 18-29 year old’s, 65% are using Snapchat, more than twice the percentage of any other age group. Why is this? One comparison between Facebook as a communication tool and Snapchat notes that Facebook uses words and clicks, befitting the use of keyboards by adults, while Snapchat’s tab bar uses icons only. Further, Snapchat’s disappearing content fits quick passage from one swipe to another, apparently valued by younger users on mobile phones.

An examination of different platforms reveals distinctive patterns of usage across demographic groups. Some of these differences appear to be design features. Others appear to be cultural adaptations that create self-supporting networks of users that share values.

The Georgetown Dialogues Initiative

Posted onOne of the learning goals stated for the undergraduate core curriculum is “…as participants in an intellectual community, students learn to … engage in difficult dialogues around challenging ideas.”

Day-to-day that learning goal is achieved by talented faculty teaching alternative perspectives to the content they’re covering, exercising skills of grappling with opposing viewpoints. Increasingly, however, students are entering Georgetown with lower capacities to engage in this kind of dialogue. Given the polarization in today’s world, it is rare for young people to witness respective dialogue among persons holding opposing viewpoints. Lacking that exposure, their capacity for such engagement can be underdeveloped. Further, the social media canceling of those who speak in opposition to any idea generates self-censorship for fear of exclusion.

We have previously announced pedagogical workshops nurturing engagement of all students in classrooms. This is one way to achieve the learning goals. We think we can do more.

Through generous financial support of alumni and parents, we are pleased to announce another way to achieve the learning goal of engaging in difficult dialogues around challenging ideas.

The Georgetown Dialogues Initiative will evolve over time with the aim of giving all Georgetown students exposure to and personal experiences in respectful dialogue between persons with opposing viewpoints.

We see great opportunities of demonstrating to students the techniques of active listening, empathy to the other’s viewpoint, presenting one’s own perspective in the same framework as the other, seeking common ground, agreeing to disagree, and ending the dialogue with appreciation for the exchange. First-year classes may be ripe opportunities for such experiences.

One course design that will be piloted over the coming year is a co-instructor format. Each instructor will take a different position on the content of the course, demonstrating the kind of dialectic across different perspectives that is fought out in annual conferences of the discipline, journals, and books over time. With two instructors in front of the class, the students will see in real time the intellectual challenges that every field experiences. As the class proceeds, the nature of the dialogue can evolve as the literature evolved, illustrating the evolution of the field’s conceptual framework. Every class will be a demonstration of “difficult dialogues around challenging ideas.”

The students will learn from the verbal exchanges how respect is communicated, despite disagreements. They will learn that disagreements do not necessarily end in shouting. Student exercises in the course will give experiential learning opportunities in this capacity.

Other courses might use the two-instructor format for only a subset of class meetings, with explicit commentary by the two instructors about how they navigated the exchange, followed by student questions about the experience.

We will engage with CNDLS and the Red House to develop a set of tools that faculty can use and guidelines that students can employ in their daily life.

Other features of the initiative that we aspire to build are large open convenings with two speakers who do not agree on some content, engaged in respectful dialogue about their differences. This will be another venue where students can be exposed to experts in such dialogic behavior. After their dialogue in front of the audience, we might have them explain their own behavior and comment on how they listen to the other speaker, how they forward their position, and how they handled disagreements.

The confrontation of opposing ideas is the essence of learning. Universities cannot achieve their mission if opposing ideas are not juxtaposed for students to evaluate. Censoring dialogue among differences within the classroom harms learning. To build the leaders of the future world, now so crippled by polarization, Georgetown needs to create an environment helping students build the capacity to be effective in interacting with those who disagree with them. Only through these skills can life-long learning take place.

Stay tuned for more news about the Georgetown Dialogues Initiative.

The Hard Work of Learning from Conflict

Posted onI ran across an aphorism from Kevin Kelly that I rather liked:

“Learn how to learn from those you disagree with or even offend you. See if you can find the truth in what they believe.”

It’s something all of us may, from time to time, think about and even try to do. It is, however, extremely difficult for most of us, I think, to make this a day-to-day practice.

Of course, there are related principles that come to mind, which might be considered prerequisites to learning from opposing viewpoints. Certainly, some empathy is required for us to consider the truth in a conflicting perspective. Listening carefully to others requires some cognitive energy. The energy is best generated by imagining oneself in another’s place. Without empathy toward the other speaker, listening itself is difficult.

But empathy, in turn, is advantaged by the Jesuit notion of the presupposition – the assumption that “those you disagree with” are acting with good will. This allows us to skip a cognitive filter — assuming that the other speaker has ill intentions in the dialogue or may be actively deceiving us. That filter stops us from listening. Instead, all we hear is our internal voice preparing our counterarguments for our next conversational turn. If we assume that the intentions of the other speaker are good-willed, then we can drop this filter.

Listening, really listening, requires effort to follow the argument. It is interesting to witness speakers practicing this art at a high level. When it comes to their turn, one often hears them say, “So I hear you saying…,” repeating the words of the other speaker, or, “let me try to paraphrase what I hear you saying…,” to determine whether they captured the intended meaning of the speaker. That act can accomplish two things: a) a signal to the other speaker that you are, indeed, attending to the conversation, and b) an act prompting clarification if a mishearing occurred. Both serve the purpose of trying to discern “the truth in what they believe.” Both also signal to the other speaker that a more specific or a more abstract presentation of their viewpoint might be more productive of our understanding.

But, unfortunately, the whole work is even more effortful than careful listening. To “learn how to learn from those you disagree with” also requires one to juxtapose one’s own truths next to the views of the speaker. Is what I’m hearing the direct opposite of what I believe; is it different but possible to integrate into my viewpoint? What might be the cause of the different viewpoint; how could I ask more about how the view was motivated? Why does the speaker believe this?

Real-time integration of new with old information may overwhelm us at the time of the dialogue. As humans, we’re not reliably that good. Here, post-dialogue reflection is often necessary. But post-dialogue reflection without an opportunity to re-engage with the other actor is inadequate. Here again, watching speakers practiced in the art of dialogue across differences, often observes, “Gee, I’d like to think more about this; this isn’t how I viewed things before…”. This is a conversational vehicle to keep the dialogue going for another round.

With another speaker who appears ready to engage, another conversation turn might say, “I see things a little differently…” then “Does this fit into your viewpoint?” followed by an expression of their own viewpoint. This is a signal that we are grappling with the content and attempting to integrate it into a synthesized understanding.

Finally, another personal attribute useful in this context is humility. Humility is required for empathy and the presupposition. Howard Baker used to say, “we have to consider the possibility that the other fella’ might be right.” This is likely the most difficult state for us to attain. If we have thought about the topic deeply over time, if we have studied the field carefully, if we have found support for our views from our network, it is difficult to imagine that all that prior work led to erroneous conclusions. This, I suspect, requires practice and never gets easy. One practice I’ve learned that experts use is exposing themselves in their day-to-day life with other viewpoints. Given the polarization of media and literature, this is easy for all of us to do; our world is organized into documentation of polar opposites. This consumption of alternative viewpoints as a practice is just another implementation of exercising the same cognitive muscles to make them stronger.

So how does all this relate to higher education? Learning from new, conflicting perspectives is the very essence of the mission of universities. Without it, nothing much happens. So it’s appropriate to continuously ask ourselves how we are nurturing our students to increase their capacities to do this.

Embracing Uncertainty

Posted onThere is much talk these days about the lack of clarity regarding our shared future. It doesn’t seem that we are living in a time for which the future is easy to predict. The ending states of various ethnic and nation-state conflicts around the world are largely unknown. Armed military operations lead to concerns about widening global conflicts. The global economy seems to be continuously disrupted by new technologies. The short and medium-term prospects regarding climate change are the source of scientific debate. The pandemic seems to be over; then, it’s not over. We’re all reminded of the need to prepare for the next pandemic, time and severity unknown.

As a university, we are consistently alerted to how this environment affects the thoughts and behaviors of our graduate and undergraduate students. In that regard, one common trait observed in some students is a seeking of explicit structure in their courses. They seek to know the rules for each feature of the class, so that they can optimize their behavior to achieve whatever are their individual goals. Most often, the goal is to maximize the grade they are given in the course. These behaviors are attempts for a very explicit reduction in uncertainty to guide behavior.

In contrast, when instructors attempt to design learning environments that resemble the lack of structure in daily life decisions, students often become uncomfortable. These courses present problems to be solved (e.g., an unanswered question, a concern raised in a community), where a textbook doesn’t exist, where the existing research findings may be inadequate, or where no specific literature exists. Such “experience-based learning” is designed to give students more capacity with “self-learning,” a skill we believe is important part of their formation. But they entail designed uncertainties.

In one sense, learning itself is a confronting of uncertainty. The student brings to the topic some prior knowledge. Sometimes, these are deeply held beliefs about certain content. Sometimes these are impressions about a new concept/technique/tool being presented in the class. The student can be confronted with a perspective that conflicts with this prior knowledge. What is true? Are the different perspectives compatible? Why is the new knowledge more valuable, in the belief of the instructor? Should the student drop their prior deeply-held beliefs? The integrative task of the learner confronts uncertainty at every turn. This uncertainty prompts discomfort as an inherent part of learning.

Fear of failure seems another unhealthy reaction to uncertainty. Thus, perfectly successful students at one level of education (e.g., high school) may face more complicated conceptual frameworks at another level. Their prior experiences of certain success are challenged. Uncertainty abounds. For those students who have never experienced failure, the situation can be deeply threatening.

As students advance in their studies, they confront alternative theories within a field. Proponents of one framework or another are generally strong in their arguments. They seek to convince the whole field of the superior value of their viewpoint. They treasure acolytes from new students in the field. Uncertainty abounds in the students’ initial exposure to alternative perspectives.

With an eye to intellectual growth, the desired reaction of facing uncertainty should be curiosity. What unknowns produce the lack of clarity of the right answer? How could one disprove or refute one perspective over another? If a new perspective challenges a strong belief for the student, how can the student scrutinize their old beliefs effectively? How does the student become open to alternative perspectives?

The undesirable reaction to uncertainty is indecision, a closing down of curiosity, or an inability to choose the next action. Such a reaction is often related to diminished ability to learn about a different way of looking at an issue. This can affect how students consumer information in course readings and lectures. It can also affect how students engage in classrooms, self-censoring their behavior in class discussions. Fear of peer negative reactions can be the stimulus for this self-censorship.

All of these concerns – fear of failure, crippling inability to choose the next action, concern about being canceled from later interpersonal interaction, self-censorship in an environment filled with diversity – may be more important now, with the deeply polarized world that robs young persons of role models of confronting alternative ways of thinking and synthesis of opposing viewpoints.

The university’s job is to construct environments where uncertainty can be confronted, with a full plunge by all students into dialogue and exchange of ideas. Over and over again, the leaders of the next generation will need the skills that they build in such environment.

Immigration and National Identity

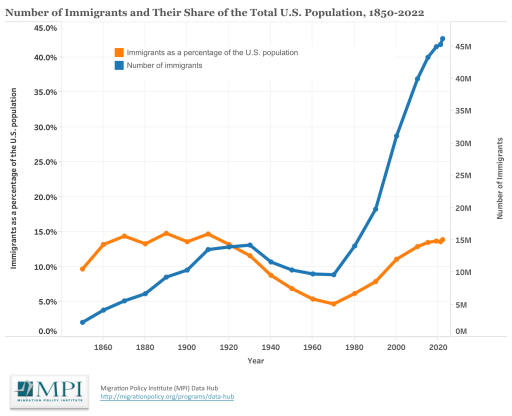

Posted onFrom its very beginning, the United States population has been shaped by immigration. The chart below gives a glimpse of what that has meant over the centuries.

The chart, from the Migration Policy Institute, has a blue line (using the right vertical axis) tracking the number in millions of immigrants to the country from 1860 to the present. In this nomenclature, “the term “immigrants” (also known as the foreign born) refers to people residing in the United States who were not U.S. citizens at birth. This population includes naturalized citizens, lawful permanent residents (LPRs), certain legal nonimmigrants (e.g., persons on student or work visas), those admitted under refugee or asylee status, and persons illegally residing in the United States.”

The numbers increase from about 2 million to about 15 million in 1930. Then there is a fifty year decline until 1970, during which the numbers of foreign born residents decline to about 10 million. Starting in 1970 there is a large increase in number all the way to the present, now above 45 million.

The orange line (using the left y-axis) represents the percentage of the total US population that are immigrants. Here the percentages hover around 15% for decades in the 19th century, dip in the middle of the 20th century and rise again to about 15% at the present time. Thus, for many decades of its existence, around 15% of the US population has been foreign born, but recent decades have experienced a return to that level from lower percentages.

Immigration from the South to the North is a global phenomenon at this time. It is a source of some tension in receiving countries, with many policy issues rising to the forefront in political debates. One interesting question related to this movement is what attributes populations consider when thinking of their national identity. How important to a society is being born in the country to considering someone a national of that country?

In that regard, a new Pew Research Center release is relevant. It reports on a multi-country survey conducted in 2023, including Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Hungary, Poland, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Australia, and the United States. There were some differences in data collection times and modes of data collection, but there is a set of questions about attitudes toward immigrants common to all the surveys.

Some of the more interesting findings surround attitudinal items about what attributes are required for deeming that someone really belongs to the resident country. More respondents across the 21 countries report that be able to speak the country’s common language is important (median across the countries, 91%). Next in the list is sharing the country’s customs and traditions (median across countries, 81%).

Relevant to the observations above regarding US immigration, the third largest percentage is “having been born in the country.” About 60% of the respondents over the various countries cite that as important in their country’s national identity. The United States is on the low end of the 23 countries for percentages of respondents who report this (50%).

There are other countries on the low end of respondents who assert being born in the country is important for national identity. They include Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, and Australia. Other countries’ respondents overwhelmingly assert that birth in the country is important for a just claim of national identity. They include Indonesia, Kenya, and Brazil.

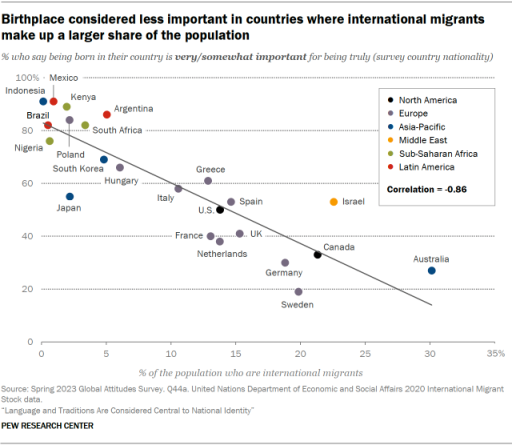

An interesting analysis across the 23 countries asks whether there is a relationship between flexibility on national identity and the percentage of a nation’s population that is not native born. The chart plots the percentage of respondents who say that being born in their country is “very” or “somewhat” important for being truly considered a national of that country.

Those countries with smaller percentages of foreign born residents have much higher percentages of respondents saying birthplace is important to national identity. In this regard, the United States respondents express attitudes expected of those countries that have around 15% of their populations born outside the country.

A few countries seem to be outliers. Respondents in Japan, with only a very small proportion of immigrants, tend to ascribe relatively low importance to birth place for national identity relative to other countries with similar proportions foreign-born. Israel, with high percentages of immigrants, places a higher than expected importance to birthplace for national identity.

These surveys a merely a point-in-time portrait of the countries’ residents. There are well-documented tensions when there are surges of immigration. (However, in examining the European countries now experiencing large in-migration, there is no evidence that birthplace is judged unusually important to their national identity.)

Overall, the analysis suggests, perhaps, good news. For countries having higher percentages of immigrants, national identify is viewed as less rooted in where one is born.

But these data do not inform the causality underlying the linkage between the two attributes in the chart above. For example, not answered by these data is when, as immigrants increase their presence, does national identity become less-rooted in birthplace. Alternatively, it is not clear whether more open cultures support larger flows of immigrants in the first place; that openness precedes the flow of immigrants. In any case, that there is larger support for foreign-born residents to be considered full nationals among those countries with more foreign-born residents is a correspondence that seems healthy for a sustainable society.

The Assumption of Order

Posted onWe’ve had a lot of weather recently in DC, leading the university to delay the start of normal class and administrative activities for a couple of days. I am fortunate to live close enough to campus to walk to my office. Hence, I was able to go to campus much before the official start of classes.

The snowfall was not much of an event relative to the typical Midwest or New England experience. Of course, in Washington, it generated a frantic rush to grocery stores for milk and toilet paper. Survivalist sentiments were common.

I walked to campus before the local neighborhood cleanup of the snow had really begun. Order had not yet return to the spaces — ice where snow had been compacted; a few inches of untouched snow elsewhere on neighborhood walks.

But as I approached the campus, I encountered a different scene. Clearly, Georgetown staff had been at work much before I arrived.

The walkways were basically clear. De-icer must have been applied much earlier in most places. Others were shoveled out.

Some of the crews were still finishing their work.

There were no students about that I could see. I assumed they were still nestled in their beds. I encountered no faculty, as classes had flipped to online delivery.

In a way, it brought back memories of the days of the pandemic when all classes were online and the vast majority of students had left campus residence halls.

On this day, the cleared walkways and work groups preparing the campus once again reminded me that Georgetown depends on a set of staff who are rarely seen by students and faculty. They show up early. They prepare the campus while most others aren’t there. On snow days, they are key to the safety of movement of all of us.

But they’re always a part of the university. They clean offices in the evenings. They are on call when pipes break, elevators get stuck, and electronic locks fail. They arrive early to prepare the foods that students, staff, and faculty consume on the campus. They prepare classroom technology for use. They get the shuttle buses warmed up and provide a way to campus. They are integral to everything that occurs at the university but are too infrequently visible for a “thank you.”

Faculty and students assume an ordered environment to do their work. It is produced, however, by many other colleagues who reestablish that environment each day. It’s only when external forces produce some disorder (like a snowstorm) that their work becomes more visible.

The university offers various gatherings and some awards for such service, but we all have a responsibility to thank those providing this work that brings order to the campus. To them, thanks for a job well done!

Update on the Initiative for Pedagogical Uses of Artificial Intelligence

Posted onThis is an update on an earlier post which announced a donor-funded initiative to incentivize use of artificial intelligence tools in Georgetown classrooms.

A request to the Georgetown community for proposals of innovative uses of AI yielded about 100 project ideas. Of those, about 40 were funded and are now in progress. It was interesting that the largest set of proposals came from the humanities faculty, with the sciences and social sciences tied for second place. Some projects were single investigator awards, labeled “IPAI Fellows;” others were groups labeled IAPI Cohorts. Some of the grants were awarded to students; most to faculty.

One useful classification system for the proposals gives a notion of where the innovation is targeted.

The first theme might be called, “Rethinking Ways of Teaching.” The funded projects display a wide variety of teaching innovation pilots. Some are examining using Large Language Models (LLMs) to display behaviors that might be harmful and then asking students to develop policy approaches to address those harms. Others approach similar issues from a purely ethical perspective. Still other work is using LLMs to generate text relevant to an assignment, assemble such material over different students and then have students attempt to identify which text was written by the LLM and which is of 100% human origin.

The second theme could be considered “Researching New Ways of Working.” Some work in this area is addressing whether AI might be used as an assistant to either instructors or students. Some AI-assistance might act as a tutor to students in the class. Others are examining whether AI might assist students in feedback on written exercises. Still others have students to first seek ideas from Chat GPT for issues tackled in the class, then develop or critique those ideas in their own work. There are several ideas of redesigning work to use LLMs as a starting point of a task, followed up with human completion. One project is examining how LLMs might be used as assistants to graders of exercises submitted by students. Another project uses plug-ins to Chat GPT to critique software written by students. A project uses LLMs to summarize scientific articles and then have the students critique the summary.

The third theme might be labeled efforts to improve the student experience as they navigate the university. In this group, some projects are using LLMs to write memoranda in a given style to seek decisions form administrators. Others are attempting to design a use case to help students scope out their curricular path through Georgetown. Still others are designing an AI tool to act as a career advisor to students or helping students navigate course registration each semester.

All of these ideas are consistent with an early decision that the Georgetown community made – to train future leaders, Georgetown must give them the capacity to use all the tools in existence to achieve the goals of people for others. Education at Georgetown must integrate new technologies in ways that achieve our centuries-old goals of formation and intellectual development of our students. AI and LLMs are just one among many tools that will be part of our students lives.

We are planning a second call for proposals for using AI in education and research at Georgetown, targeting a Mid-March 2024 announcement. We also plan to launch a Design Lab with activities from January to April to help prepare faculty to apply for the second round of grants, and to build the community of grantees in sharing with each other and broader faculty, staff and students. Activities to include design sessions, invited speakers, and panel discussions. All these efforts are led by Eddie Maloney of CNDLS and Randy Bass of the Red House.

Humility and the Scholar’s Life

Posted onI have a vivid memory of guiding a PhD student’s consideration of a dissertation topic some years ago. The plan started out as tackling multiple current controversies in the field and then unifying the solutions into a new theory. There was conceptual work, data collection, and statistical analysis involved. The student was very bright and a strong performer in graduate classes, but all signs pointed to dangers.

The memorability of the events stem from the length of time required to pare down the student’s ambitions. Over weeks, we together probed in detail each of the controversies the student aspired to solve, in long talks about necessary arguments and evidence. Of course, these talks were dispiriting for the student, as piece by piece, the plan to renovate the entire field melted away.

Eventually, however, a new plan emerged — a solid, novel, do-able contribution to the field. The student executed the plan competently and succeed in defending the dissertation on time.

I recall a similar lesson for myself — research requires a deep humility to succeed.

That last sentence itself may seem to contradict the examples of scientific and creative pathbreaking achievements that are easily documented (cubism in art, the Higgs Boson experimental evidence). On their surface, these don’t seem to be based on humility by the scholars. Achieving dramatic breakthroughs often, in retrospect, is the culmination of many prior failures and many prior small successes. Indeed, the roots of transformative research results often lie in findings that are humble building blocks. While the “north star” of the research might be quite bold and transformative, the constituent work is not.

So, to clarify, humility is not necessarily useful when determining the question or challenge to pursue in one’s scholarship. Instead, bold thinking is often required. However, the humility is required in discerning what questions or challenges are both important to pursue and amenable to success. Indeed, one of the rarest traits in those new to research is identifying a question that is possible to answer, but whose answer will be an important contribution to human understanding.

This may be an asset in most human endeavors, not just research. I once asked a CEO of a large enterprise what were his greatest challenges in growing the company. He answered that it was hiring staff that asked the right questions. Once the question was articulated, it was much easier for him to find the way forward. So too, with research. A large part of success requires discerning the right question.

What’s the evidence of the need for humility? After all, the apparent arrogance of intellectual elites is well-documented. They don’t appear too humble to the average person. To combat that tendency, fields often have strong norms of reporting limitations of the research reported. This is common to fields that are article-based, often with papers ending with sections labeled “Limitations” followed by “Summary.” Of course, in seminar presentations among academic peers, much of the session is given to give-and-take critiques of the results. That context also brings some humility to the behavior of academics, albeit with less self-generated features. More generally, peer-review is often an external influence on humility.

In short, bold aspirations are often important to sustaining energy for the research. But approaching one’s research with humility is an assist to avoiding overreach. A subordination of one’s ego to the work of the research often supports the day-to-day research activities despite their humble immediate goals.

Why Universities Grow

Posted onDiscussions over holiday dinner tables led to an interesting set of observations about growth over time in universities throughout the world. Some observations noted how post-secondary education appears to be viewed as a key driver to the societal development in many countries. Often these are direct investments of national governments. The expansion of universities in China and India are examples.

Some of this growth might also be an indirect effect of globalization, as enterprises operating in multiple nations seek to build local staffs with skills suitable to sophisticated supply chains. Having local staff deeply knowledgeable of the culture and regulatory environment has corporate advantages. The desired operations’ knowledge and technical skills, however, are often those that demand university educations. Global firms create demand for university graduates wherever they operate.

Increasingly, universities’ service to local communities is being recognized. Colleges and universities create clusters of spinoff organizations that benefit the job market, economic tax base, cultural richness, and vibrancy of a community. Some faculty create businesses. Graduates tend to stay in town and build their careers locally. For land-grant universities, direct support of agricultural activities are part of their mission. For universities that have schools of medicine and associated hospitals, the quality of community health care can be enhanced. Such services increase demand for more.

All of these features of post-secondary education institutions contribute to their growth.

However, many of the above are the indirect effects of an essential attribute of research universities. These are the institutions that continuously add to human knowledge and insight. University research and scholarship build future societies. Basic research produces the deeper understanding of features of the natural world. Later, sometimes decades later, new products implementing the findings are given to the world, making lives easier and more fulfilling. The arts and humanities constantly innovate and create new ways to appreciate life and express deep emotions central to being human.

In the last 100 years, this type of research has created whole new fields of knowledge. Research tends to accumulate. It may start out with new theories, followed by developments and scholarship that support them. As theories move to applications, in the sciences and social sciences, research teams often emerge. They form research centers or institutes, with the mission to enhance understanding and application of the new findings. Growth of research universities disproportionately begins with new research programs.

As the fields mature, new occupational families arise. Witness digital journalism, data science, neuroscience, bioethics, environmental studies, international diplomacy, and media studies. As new occupations arise, students interested in them seek formal training to prepare themselves for such careers. New academic degree programs emerge to serve the demand for the occupations.

Human knowledge doesn’t seem to atrophy or decline over time. “Old” knowledge still exists and remains a stimulus to new knowledge. “Old” fields continue to evolve, often in spurts of creativity and intellectual turmoil, to achieve new insights. Of course, research efforts that do not yield positive outcomes are ended by negative peer reviews, and the scholar turns to other efforts.

Hence, it is more common for universities to evolve new features, not to destroy existing features. This attribute distinguishes universities from private sector enterprises solely focused on profit maximization, which tend to drop unpopular services or products. There is, of course, an ebb and flow in demand for courses in various fields. However, those productive of knowledge of how the natural world works, how societies and individuals behave, are the producers of basic insights that enhance future lives.

As knowledge expands, universities tend to expand. Successful knowledge expansion is supported; lack of success dies out of its own accord. Fields merge and morph. The wisdom needed to support universities over time requires deep understanding of the life course of new ideas as they move from radical new thoughts, to cohesive theories, to replicated research support, to everyday applications that no one even associates with research.

Office of the ProvostBox 571014 650 ICC37th and O Streets, N.W., Washington D.C. 20057Phone: (202) 687.6400Fax: (202) 687.5103provost@georgetown.edu

Connect with us via: