Resilience: “1620s, ‘act of rebounding or springing back,’ often of immaterial things, from Latin resiliens, present participle of resilire ‘to rebound, recoil,’ from re- ‘back’ (see re-) + salire ‘to jump, leap’ (see salient (adj.)). Compare result (v.). In physical sciences, the meaning ‘elasticity, power of returning to original shape after compression, etc.’ is by 1824.” (Online Etymology Dictionary, www.etymonline.com, accessed December 20, 2023)

This notion of a power within a physical entity to return to its original shape might also be an attractive way to think about human resilience. In that regard, Nietzsche is said to have noted, “That which does not kill us makes us stronger.” (During COVID, there was a darker version of this thought going around, “That which does not kill you, mutates to try again.” I like Nietzsche’s version.)

A significant part of a university’s mission is to build the future leaders of society. Many of us believe that all lives bring challenges. Further, those armed with the skills to recover from failure eventually lead more fulfilling lives. Leadership requires resilience. Certainly, future leaders need to have the power within themselves to return to their original state without lasting harm after tragic events.

The “re-“ part of resilience is thus important to the notion. The attribute requires the experience of “compression” followed by the “power” to return to original state. Without compression, there is no need for bouncing back.

All of these thoughts arose in musing about whether and how the university can build resilience in students.

The increasing sense of isolation, of anxiety and depression, that is common in post-pandemic society is not a societal strength at this historical moment. Certainly, the function of supporting students with mental health impairments seeks to build the capacity of bouncing back to an earlier state. In that sense, the goal of mental health services is to eliminate the need for them. However, while the prevalence of such impairments is larger than was evident 20 years ago, it still remains a minority of students’ experiences.

Of greater prevalence may be high-performing students who have never experienced failure prior to coming to Georgetown. Georgetown, like many selective universities, enjoys the presence of exemplary students taught by outstanding faculty. However, it produces feedback to students regarding their performance that is rather homogeneous, with grades clustering around B+ to A. Of course, there are exceptions, but it doesn’t seem that many students are receiving low grades. Therefore, grades do not tend to supply the failures from which they must bounce back.

At some universities, there are formal courses in resilience. Based on a quick perusal of accessible syllabi, such courses seem to emphasize mindfulness, self-awareness, positive thinking, self-care and similar concepts. The readings describe meditative techniques and case studies of people who have overcome challenges to their well-being.

One wonders whether reading about a resilient person builds resilience in the reader. Can the acquisition of skills of resilience be acquired removed from the personal experience of challenge/failure/crisis?

There are Georgetown colleagues who design their courses to include situations building resilience. Some design early exercises that are severe challenges to the beginning student, followed by showing the way to correct the poor performance in later exercises.

Other courses use experience-based learning with iterations of group project work, allowing the failure of initial versions to be repaired in later versions. Looking at these, it seems logical that courses that teach problem-solving skills without simple structured answers might be useful in building resilience.

I recall one course that presented students with a real-world problem to be solved. The students were assigned to groups. The syllabus had no readings. There were no lectures. There were no toy solutions discussed. The group was on its own. The students soon realized that they needed to read something about the problem, to learn about past solutions in other domains, to synthesize alternative viewpoints, etc. The attractive feature of that learning environment was the lack of structure. It forced students to create approaches. Such experiences seem to mimic some of the features of resilience, but in a safe environment, with an instructor nearby to assist in “springing back” from intermediate failures.

Courses that present conflicting perspectives on the same material might build a type of intellectual resilience. This is often most effectively arranged around active debates ongoing in a field, where the matters are not yet resolved. In co-teaching formats, one instructor can take on the role of the advocate for one perspective and the other, another. Students get engaged to “bounce back” from a critique from one side versus another. They face the adversity of a different perspective and reflect on how to counter it. Alternatively, they synthesize the other perspective into a hybrid of two differing ones.

How else can the learning we seek for our students be designed to increase their resilience to future life challenges?

Address

ICC 650

Box 571014

37th & O St, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20057

Contact

Phone: (202) 687.6400

Email: provost@georgetown.edu

What’s Happening with US Production of Doctorates

Posted onEvery year the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics conducts a census of persons who received a doctorate degree, call the Survey of Earned Doctorates. Over the years, the survey provides a unique view into trends in educating doctoral degree scholars in the country.

The 2022 results were recently released in a report, accompanied by detailed tables. For those of us who focus day-to-day on our own graduate programs, it’s useful from time to time to see national trends.

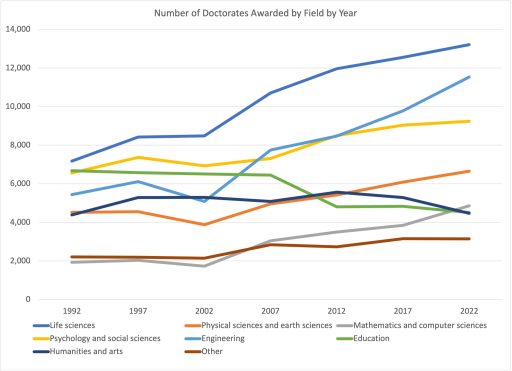

The first important result is that the number of doctorate recipients tends to increase year over year. For example, in 2022 there were roughly 58,000 new doctorate recipients, compared to roughly 39,000 in 1992. It is important to note that the 2022 increase followed two years of decline, probably pandemic-affected. The greatest increases in recent years occur in the life sciences, especially biomedical PhD’s, and also those in engineering. In contrast to these two fields, Education doctorates and doctorates in the Humanities and the Arts, show lower or no increases over recent years.

The 2022 survey added some questions about perceived effects of the pandemic on the respondent’s progress toward degree. Over two-thirds of the respondents reported that their doctoral research was disrupted by the pandemic. About half of the respondents noted that this disruption slowed their completion of the degree. Those fields whose research is dependent on laboratories, studios or other facilities reported the highest disruption of their progress. In contrast, those in fields that don’t require such physical facilities reported less disruption (e.g., mathematics and computer science). Despite these reports, over the years, the overall time to degree among these doctorate recipients show no large increases. Indeed, there is some evidence that the PhD time to degree is shorter in 2022 than in prior years.

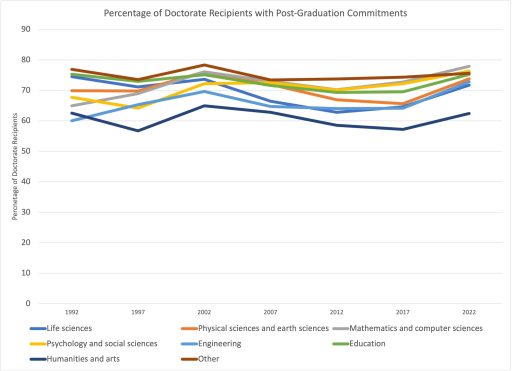

Another issue of preeminence importance to both faculty and students in PhD programs is the employment outcome of the programs. The survey asked the respondents to report whether upon receipt of the degree they had a commitment for employment, including a postdoctoral fellow appointment. The chart below again compares different fields over time. Roughly 65-75% of all doctorate recipients report having a job commitment. Further, there is an increase in these percentages overall between the 2017-2022. However, there are field differences. Quite consistently, the doctorate recipients in the humanities and arts have lower job commitments upon completion of their programs.

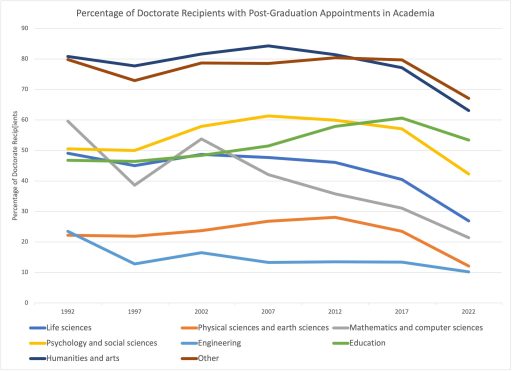

What kinds of jobs are the new doctorate recipients taking? Universities and colleges form a traditional sector of employment of PhD’s. The chart below shows an overall decline in the percentage of academic appointments for new PhD’s between 2017 and 2022. That is, employment of PhD’s is spreading to nonacademic locations.

The trends below show very large field differences in the tendency to have academic employment. The lowest percentages employed in academia are for fields of engineering as well as the physical and earth sciences. PhD’s from these fields disproportionately work in research and development positions in private industry. In contrast, the humanities and arts new PhD’s are employed in academia post-graduation at very high percentages, near 80%. (Note that the “Other” category also tends to be employed in academia; these include among others PhD’s in business administration.).

But even those fields traditionally hired by universities are seeing shifts. For example, while only 4% of humanities and arts new PhD’s were hired by the private sector in 1992, by 2022 the percentage was 11%.

The overall findings over time of lower employment rates in academia are likely to increase as the age distribution of the US suggests lower enrollments in colleges in the future. (See this post.)

The doctoral degree is typically the highest research-oriented degree offered in US universities. Our country continues to produce new PhD’s in high numbers but the growth in biomedical and engineering PhD’s suggest that the production is linked to demand from private sector firms. There is never a perfect match between demand for PhD’s in a given field and the production of new PhD’s in that field. For practical and ethical reasons, it behooves all of us to examine data like those from the Survey of Earned Doctorates.

Celebrating Internal Research Support

Posted onThis Monday, there was a wonderful in-person gathering in the Bioethics Library of a set of faculty who have been awarded different internal grants to support their research. Colleagues met in the same room, rediscovering shared interests and learning about new research projects.

We have run such competitions for internal grants for some years. This year 133 faculty submitted proposals for research support. A group of peer faculty reviewers read these proposals – 400 reviews in total. In short, this is a large enterprise with rigorous peer review. It is an important signal of the commitment of the university to faculty research.

Twenty faculty received summer salary supplement grants. The Summer Salary Supplement (SSS) Program provides support for two months of work on a research or creative arts project between June and August. An SSS consists of $10,000 in taxable income (plus fringe). If a faculty member receives other summer salary support, from either external or university sources, the SSS will be adjusted so that the total salary support does not exceed 2/9ths of the faculty member’s academic year salary.

The projects being supported among the 20 faculty members are quite diverse. They include one study using quantitative modeling combined with qualitative process tracing to investigate the relationship between armed conflict, identity, economic development, and election outcomes in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to another study of how nation-state climate policy is affecting trade among nations mounted by a Georgetown faculty member collaborating with scholars in Germany and Uganda.

Eleven faculty were awarded annual research grants. The Annual Research Grant (ARG) Program provides support for non-salary expenses incurred in the conduct of a specific research or scholarship project. An ARG provides between $5,000 and $10,000 in funding to facilitate new or on-going research or scholarship that could not be conducted or completed without the support. Awards are made in the Fall semester, to cover expenses incurred through the end of the following summer.

These projects ranged from a historical data collection for a book project describing the multi-generation effects of a wealthy mining family on global capitalism to a study of how nanoparticles might be used for drug delivery of active pharmaceutical ingredients inside the human body to another on how computer vision algorithms often employed in artificial intelligence can be affected by small occlusions in the image.

Twenty faculty were award research leaves. The Georgetown University Research Leave (GURL) Program provides one semester of leave for tenure line faculty to conduct research or scholarship, or to work on a project in the creative arts. GURLs provide one semester of leave, free of all teaching and service obligations, to tenure line faculty at any rank – Assistant, Associate, or Full Professor. Awards are made in the Fall semester, to be taken in the Fall or Spring of the following academic year.

One leave will permit work on a critical edition of Cimarosa’s comic La ballerina amante by working in the Library of the Conservatory of Naples, the State Archives, the Biblioteca della Storia Patria and the Archivio Storico del Banco di Napoli. Another will focus on how tariff increases from China and the US have affected the location of multinational firm activity.

Although the above mention just a few of the research activities supported by the internal grants, one quickly gets a sense of how varied is the scholarship at a research university. It is gratifying to see how many of our colleagues are working at the cutting edge of their fields, tackling important gaps in our understanding of our world, its past, present, and future.

What is Teaching?

Posted onIt is customary to describe the role of universities as involving three components. Teaching or forming the next generation through instruction is one. Another is the discovery of new knowledge, the development of new ideas or theory, or innovation in the application of existing knowledge. Finally, universities have a role in serving those external to the university; indeed, the whole world, including the physical world, but also the economies, the societies, and event virtual worlds.

Of course these three missions are a joint enterprise of faculty, staff, and students.

Over the past few years, there have been attempts to unbundle the three missions of education, research, and service. For example, ten years ago there was a clear attack to remove research from teaching, by massive open online courses, the birth of Coursera and EdX and others. These were instruction-only enterprises. They also stripped higher education of its service orientation to the larger world.

The bundling of the three missions has been maintained by universities that have a clear research mission. In such domains, faculty who teach are often heavily involved in research. For example, land grant universities in the US have maintained their mission to serve the states in which they are located. Jesuit colleges and universities have explicit missions to serve outside populations especially those relatively disadvantaged.

This is a post about work to enhance the bundling of the research and teaching missions of a university.

I became a lab research assistant in a social science computer room as a college sophomore. I worked for a faculty member in sociology who was building a statistical analysis platform for empirical social scientists. I needed the money. I did not seek the job as a way to learn anything new. But it sneaked up on me. I began doing minor tasks under the direction of the faculty member. I helped other students navigate the lab equipment. I was given increasingly complex tasks. They were immense fun. I got hooked on the whole research enterprise. I stayed over the summer and coded various modules in the software. I helped the faculty member in some analysis. I received an insight into the humanity and intellectual passion of faculty – something I never received in the classroom.

More and more Georgetown faculty are attempting to integrate their research lives with their instructional lives. Of course, those involved in the oversight of PhD students often achieve strong overlap between their own research and that of the PhD mentees. The mentor might be conducting a multifaceted research program, years or decades in its conception. PhD students identify a component of that research program that becomes a key feature of their dissertation.

But in reviewing the curricula vitae of my colleagues for promotion and tenure nominations, it’s clear that not just predoctoral students but also undergraduates and masters students are collaborators with Georgetown faculty. Joint articles with students seem to be more and more common. Ongoing collaborations with graduates are less rare than previously. From the research statements of the faculty dossiers, it’s clear that such strategies of the faculty have achieved an integration of teaching and research that benefits the faculty member’s productivity.

In the podcasts, Faculty in Research, it is clear that our most productive faculty have achieved an integration of research and teaching that makes the two missions not competitive but synergistic. They credit teaching with enhancing their research agendas; they credit working with students in research activities as a tool of enhanced creativity. They see the research mentoring of students as an important extension of their educational role.

From the student perspective, it seems clear that such collaborations generate a richer learning experience than could ever be achieved in the classroom alone. They can offer the student insight into the moment of discovery or the moment of creation that is the magic elixir of all faculty scholarly activity. The joy of those moments can seal into the student’s memory the key lessons of self-teaching and probing inquiry that serve their full lifetimes.

Giving Thanks

Posted onWhile there are other countries that have national days giving thanks for one or another features of life, America’s Thanksgiving seems to be unusual in its devotion to the consumption of large amounts of food on its day of thanks.

My favorite memory of Thanksgiving was launched when I was about 9 years old. My father, for his October birthday had received a small tape recorder, the old version with two reels of tape and a small microphone attached with a cord. The Thanksgiving feast that year was traditional, with a large turkey, dressing, cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, green bean casserole, and probably a mandarin orange Jell-O salad. Around the table were our neighbors, their child, my grandparents, all four of us children, and my mother and father. I and the men at the table were dressed in coats and tie; my sisters wore their Sunday best dresses.

In a secret act of mischief, my father had placed the tape recorder underneath the table, with the microphone hidden in the centerpiece. His idea was to record the conversation throughout the meal and then, in his notion of post-dinner entertainment, have all of us listen to the conversation.

So the meal proceeded. The food, as always was great. Spirits were high; fun was had by all. Old stories were retold. The generations exchanged their world views. Bonding was renewed.

It came time for my father’s reveal of his deceptive act. He confessed to his secret and pulled out the tape recorder and placed it on the table.

Well, it turned out the technology was not up to his intention. As the tape played, there were muffled voices overlapping one another. The overlapping conversations yielded a persistent garble. There was clearly human vocal interaction but most was incomprehensible.

Indeed, throughout the meal, only one voice was consistently understandable. It was the high pitched voice of my younger sister, the fourth of four siblings, then about 5 years old. Near the beginning of the meal, she said “Please pass the salt” in a very clear voice. Mumbled adult voices. A few minutes later, you hear the little voice “Please pass the salt” in a slightly louder voice. More mumbled adult voices. A few minutes later, “Please pass the salt”. This time a little softer. Mumble, mumble, mumble. “Please pass the salt.” By the end of the meal, there was no audio evidence that salt was ever provided to her.

As she became the heroine of the event, this was my first lesson in perseverance, grit, resilience, and, I guess, a salt-free diet.

Happy Thanksgiving to all!

A Denominator, a Denominator, my Conclusion for a Denominator!

Posted on(My apologies to Richard III)

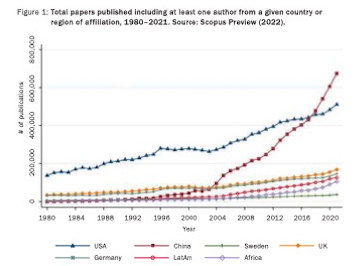

Earlier posts have opined on the rise of China’s higher education infrastructure and its increase in research article production in the mid-2010’s, exponential growth that surpassed the volume of US scientific publications.

A report from STINT, the Stiftelsen för internationalisering av högre utbildning och forskning in Sweden

takes advantage of Scopus, a database tracking about 34,000 peer-reviewed journals in life sciences, social sciences, physical sciences, and health sciences. The report studies the period 1980-2021.

First, the report again documented the exponential growth of scholarly publications from China, as shown below in the figure labeled Figure 1. This phenomenon has been the focus of much discussion probing the causes of this change (e.g., incentives to publish), further analysis on the impact of papers (e.g., citation rates), and implications for national competition.

Second, during these years, an important additional trend was developing – greater collaboration among scholars in different countries.

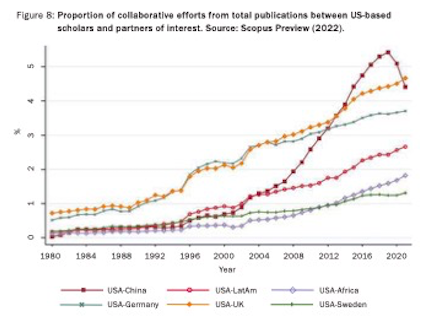

The figure below (labeled Figure 8) from the STINT report, shows the percentage of collaborative publications between US research and colleagues in other countries. The y-axis is the percentage of all papers published by scholars in two given countries that were collaborative across two pairs of country’s scholars.

The first conclusion of the trends is that the tendency of US scientists to collaborate with colleagues in other counties increases during this time period, especially from 1998 onward. There are many changes that took place in this period, including the ubiquitous use of the internet and greater nation-state support of international collaboration.

Notice, however, the sharp decline in the last three years of the USA-China percentages.

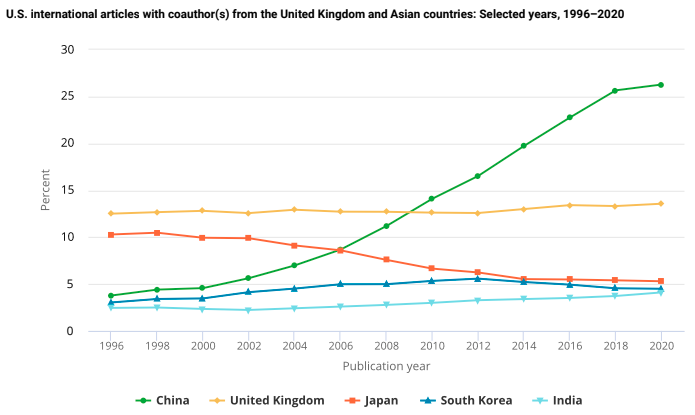

Another report, from the US National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) uses data from the same Scopus source. Figure PBS-5, from that report, plots co-authored papers between US scholars and those from other countries. The green line shows the same dramatic increase in US-China collaborative publications as the STINT data, but no dramatic decline over the most recent years that was evident in Figure 8 above.

Why do these two charts imply different trends?

First, the number of scholarly publications is increasing rapidly among Chinese scholars, quite sharp and exponential growth, especially since 2010 or so. Growth in the number of articles by US researchers is also increasing, but at a much lower rate of increase over the years.

The STINT Figure 8 divides the number of co-authored US-Chinese publications by the sum of total publications by US scholars and the total by Chinese scholars. The NCSES Figure PBS-5 divides the number of co-authored publications only by the total number of US authored publications.

When the number of collaborations are divided by the number of total US publications, the percentage of US-scholar articles co-authored with Chinese scholars is not declining. However, when the number of collaborations are divided by the total of US and Chinese scholar articles, the percentages are rapidly declining. In other words, Chinese co-authors are a larger proportion of US-scholars’ work. But US co-authors are a smaller proportion of Chinese scholars work. (Further STINT work shows this clearly.).

By the way, there is some indication that Chinese-European collaboration is also weakening. The STINT report cites new proposed laws in some European countries restricting such collaborations.

Denominators make a difference in conclusions about patterns. In this little example, the country currently exhibiting the largest global research product, China, is doing so with smaller percentages of work collaborative with US scholars. From the perspective of the US scientific product, the percentage of collaborations with Chinese scholars has not declined. But scholarly collaborations have not increased proportionately among US scholars to accompany the rapid growth of Chinese scholarship. Chinese scholars’ product seems less dependent on the US than was true in earlier years.

The Youth of the Future and the University of the Future

Posted onWhile all of us in higher education are fully focused on the present needs of those we serve (students, faculty, others), we must also acknowledge that universities will likely persist as key institutions in society for many decades in the future. In that sense, a look ahead at population trends is relevant to advance planning.

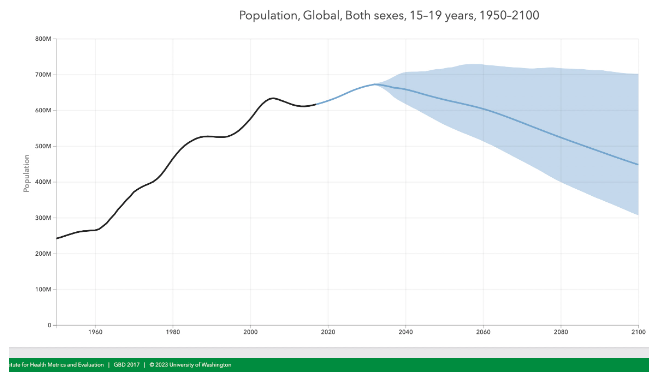

One of the surprising forecasts (to many) is that the total youth (15-19 years of age) population is plateauing over time, with a likelihood of decline in the coming decades. This follows the reduction in fertility rates reflecting modernization, female labor force participation, and widespread contraceptive use. For example, the forecast from the University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation for global population of such youth is notable.

The chart below is a presentation of estimates of global population of 15-19 year old’s. The light blue fan-shaped pattern for out-years reflects the uncertainty of the forecast (like that common to hurricane forecasts), dependent on estimates of fertility rates, cross-border migration, mortality rates, government policies, etc. The important point is that there is some consensus in the estimates for a decline in the population, starting between 2030-2040.

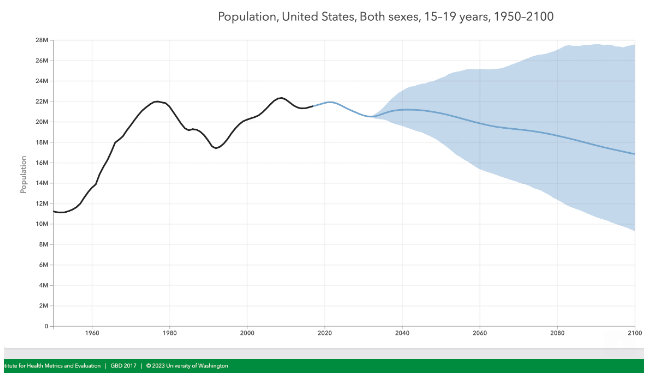

That’s the forecast globally, but US universities are most directly affected by our own in-country population. What are the equivalent forecasts for the United States population? The chart below provides that forecast. There is a well-established agreement of a dip in the coming few decades, followed by a little jump. In short, however, there is a similar form, albeit a shallower decline than the global forecasts. Again, the forecasts have larger ranges of uncertainty as time proceeds. But the US figures suggests a drop in this decade followed by a small jump up around 2040, followed by a slow decline. How these number translate into enrollments in higher education, of course, is complicated by all of the drivers of whether young people seek to enroll in college (e.g., parental guidance, costs relative to income, cultural supports for the value of higher education).

The US has a disproportionate share of the world’s higher education universities, and some of them are the strongest in the world. Because of that, many US universities have welcomed students from other countries to their student bodies. Two large countries, China and India, have formed a major part of this student population coming to the US for their education. Indeed, for decades the United States has enjoyed great benefits of the strong students from these countries who, upon graduation, stay to enrich our society and economy with their talents. But the demographics of these two countries are changing also.

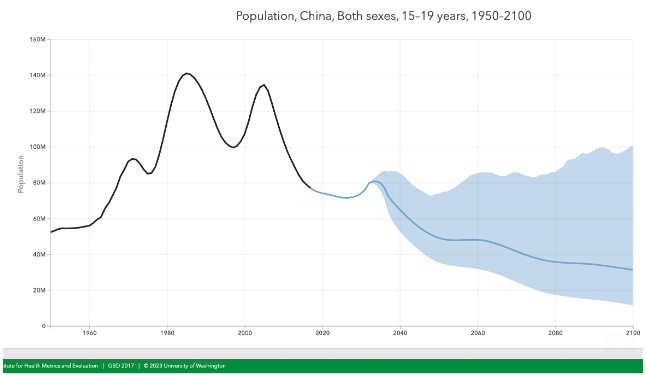

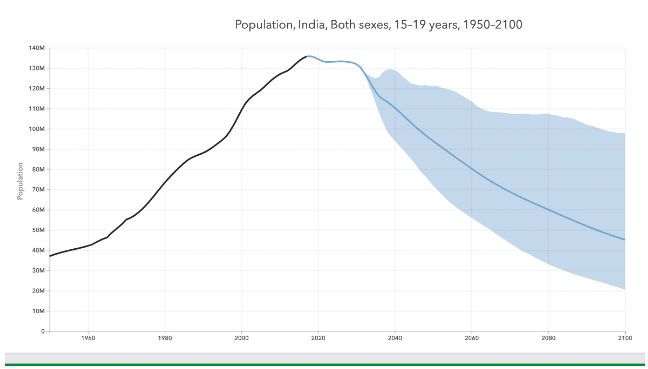

These graphs show expectation that both China and India will experience declines in the youths 15-19 years old in the 2030-2040 time period. At the same time, both countries are investing in developing their own strong higher education sectors. It is logical to expect declines in students from these countries over this period.

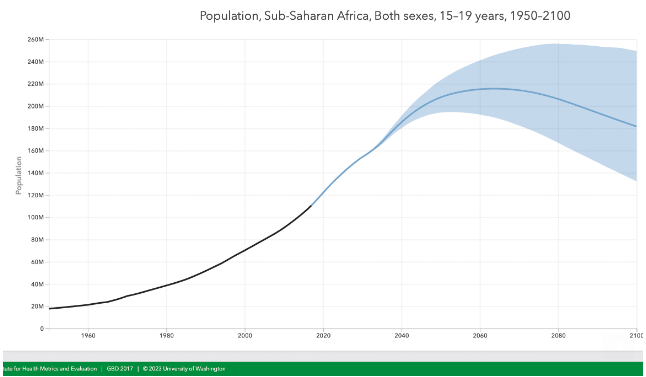

If there is an area of the world that appears to have different trends, it is Sub-Saharan Africa. There the forecasts suggests growth in the youth population through about 2060. Following that, there is a decline, given the model assumptions. Africa’s population will remain a growing source of youth for about 20 years later than the other countries described above.

What does all this mean for universities? For the US, while declines in the youth population are forecasted, they are not as dramatic as those in other countries. The fertility rates of immigrant populations are larger than those of populations born in the US. Thus, it seems clear that youth from the populations immigrating to the US will be increasingly important to universities. Much depends on immigration.

While China and India are important sources of students in US higher education, the demographic profiles of the countries suggest that the coming decades will see declines, other things being equal. The radically different age profile of Sub-Saharan Africa suggests that it could become a more prominent source of international students for US institutions, other things being equal.

Finally, but not relevant to the graphs above, it is likely that the youth of today will live much longer lives than those of earlier generations. If the rate of technological change continues at the pace of today, they will encounter the need to retool, the learn new areas, multiple times throughout their lives. The effect of this may be a refocusing of higher education to cohorts of students older than those traditional for residential four-year universities. This might dampen effects of shrinking youth populations.

In short, the supply of young persons eligible for higher education is changing. The future rate of change is smaller in the US than in China and India. Sub-Saharan Africa will be a younger population for a longer time period than China and India. Life expectancy is growing; new populations of potential higher education entrants may emerge. It seems wise for the design of institutions of higher education to reflect these changes in supply and demand.

Georgetown Faces

Posted onEarlier posts have commented on the occupational stratification in universities, here, here, here, and here. The central theme was that any university community, although centered around faculty and students, cannot function without a large number of staff, professional, skilled, and unskilled, who collectively create the environment that permits faculty and students to do their joint work.

The posts tried to make the point that much of the external attention on universities is disproportionately focused on the experiences of students and faculty. The scientific popular press highlights new discoveries of university laboratories. Economic journalists seek quotes from business and economics faculty on the latest moves of the economy. Sports journalists highlight the performance of intercollegiate athletes. Multiple media channels post stories of individual students, especially those who overcame obstacles or created innovations that could change the world. University web sites clearly communicate that being an undergraduate at the school is one of the greatest opportunities a young person could imagine.

Yet every building on any campus, every sidewalk, every classroom, every restroom needs care. Plumbing breaks. Leaves fall from trees. Flowers need to be replanted. Windows need to be washed. Students need answers to how they navigate the campus rules. Students need guidance on fitness and intramural sports activities. Students and faculty have mental health service demands. Faculty and students generate trash that needs to be removed after the day’s work. Personal computers break; classroom technologies need calibration and fixes. Office supplies run out. Xerox machines break down. Residence halls have thousands of rooms that need cleaning, ovens that need repairs, refrigerators that break down, ovens that fail. The safety of students and faculty needs attention and oversight. Buses move students and faculty to diverse sites.

In short, universities are like small cities. They supply housing, transportation, food, entertainment, exercise facilties, health care delivery, police protections, IT infrastructure, office buildings, and laboratories. Of course, all of these serve students and faculty, but activities are rarely mentioned in the public communication by the university.

Given these observations, it is heartwarming that the Georgetown Office of Communications has re-energized a service to the entire University community. There were short profiles of staff built up over time, labeled “Georgetown Faces.” We should all revisit the site. They posts taught the reader how varied staff’s work was key to the functioning of the university. The COVID years greatly complicated the continuation of this service to the community, but it’s back in action now.

A wonderful feature of its renewal is that each member of the community can nominate someone they interact with, someone who shows consistent high performance and commitment to Georgetown. Any Georgetown community member can forward a nomination, to propose honoring a staff colleague with a “Georgetown Faces” spotlight. Go here to nominate a valued colleague.

I know we have many, many colleagues whose work matters to the fulfillment of the mission of the university. Too few of us know about them. Nominate one that you know.

Values and AI Safety

Posted onWe are witnessing an interesting moment in use of artificial intelligence systems, especially those reflecting Large Language Models (LLMs) and generative features, like Chat GPT-4 and Bard.

Many of the issues of potential harm are well documented – bias due to poor training data, malicious use, privacy concerns, environmental impacts of data centers, and vulnerability to cyberattacks. Another concern that has less visibility is the violation of norms and values of users.

This latter is one of the issues that arise under the label of “safety” of LLM’s. Some of this work is attempting to reduce the output from LLMs that offend the user’s values.

What are the key issues regarding safety for AI in general? A new white paper from the Center for Security and Emerging Technologies addresses AI systems more generally and notes three key concepts, all focused on the nature of the learning algorithms. First, one challenge is building a system to self-assess the confidence with which it is making its prediction – sometimes called the robustness of the system. When the confidence is low, then it is desirable to have some fallback option or human intervention. Second, another desirable feature of an AI system is that humans are able to understand or interpret the behavior of the system. Ideally, this is an understanding of how new inputs to the system will inform its future predictions. Third, the term “specification” is sometimes used to measure the alignment of the AI performance to the goals of the designer.

This last seems relevant to generative AI applications with LLMs. Some developers note that initial post-training LLMs’ outputs are offensive to social norms and commonly-held beliefs and values of the likely users (e.g., racist, misogynistic, or aggressive output). It appears that common guidance is to have some review after the learning step is complete, either by a human or through additional algorithms. Additional training is then introduced to assure the given norms are followed in a revised platform.

It is this step that is interesting from a digital ethics perspective. Although is its referred to as a “safety” step, it is really the imposition of human values as perceived by those doing the evaluation. It occurs after the main content training is completed. However, what norms and/or values constitute the evaluation step do not appear to be widely-documented. It appears that for some cases, the developers and overseers of the original training step are conducting the evaluation. What values guided their decisions are largely unknown.

Even the developers often acknowledge that not all offensive behavior can be eliminated through these internal steps. Thus, after the release of the platform, users are commonly asked to report other examples of offensive or erroneous outputs.

What seems to be missing in the current environment is a community articulation of what values should be upheld in the performance of the platform and which are not to be policed. This might be viewed not as a post-construction patch, but a full design principle.

Further, most users are unaware of what additional evaluative steps have been executed to “clean up” the behavior of the platform. Thus, the change worth discussing is explicit statement and documentation of values, as well as their incorporation into the original platform design.

In one sense, the evaluative steps now in place are attempting to exercise community standards without community input. The values guiding the evaluation step are largely undocumented. They are patches after a design has been implemented. It seems like ripe territory for advances.

Provost Office Faculty Awards

Posted onEvery year, through rigorous reviews by panels of fellow faculty, we honor those among us who model the success that all academics seek. On November 9, we will celebrate these colleagues with a more formal ceremony (as well as this year’s Provost Distinguished Associate Professors previously announced here ), but this post reveals those who will carry these honors this year.

Provost Innovation in Teaching Award:

Pam Biernacki, DNP, FNP-BC, Associate Professor, GU School of Nursing

Lois Wessel, DNP, FNP-BC, Professor, GU School of Nursing

Elke Zschaebitz, DNP, ARPN, Assistant Professor, GU School of Nursing

The Virtual Interprofessional Education (VIPE) Consortium, created at several universities including Georgetown School of Nursing, developed an educational method that can be shared and replicated to create online, interprofessional experiences using a virtual communications/meeting platform, such as Zoom or Teams. The VIPE program is grounded in several learning theories, problem-based learning, and case-based learning, as well as the notion that IPE and collaborative practice lend themselves to collaborative problem solving where there is not one single correct solution, encouraging students to solve problems in the context of a collaborative interprofessional group.

Career Research Achievement Award:

Suzanne Stetkevych, Ph.D, Professor, College of Arts & Sciences

Prof. Stetkevych joined the Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies in 2012, and was named the Sultan Qaboos bin Said Chair in 2014. Prof. Stetkevych has produced four landmark volumes in the study of Arabic poetry. In addition to these books, Prof. Stetkevych has produced a steady stream of forty peer-reviewed articles and book chapters. These have appeared in the premier journals for Arabic literature and Arabic and Islamic history and elsewhere. Additionally, she served dynamically as the editor of one of the field’s two scholarly journals (The Journal of Arabic Literature) for a decade. Many of her former students are now tenured faculty across North America, Europe and the Arab world. She has received grants and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Fulbright Foundation, the Social Science Research Council, the American Research Center in Egypt, the American Center for Oriental Research in Jordan, and others. In 2017, she won the Middle East Medievalists Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2019 she and her husband were co-awarded the coveted Sheikh Zayed Book Award. Last year, Prof. Stetkevych received a truly massive honor — the King Faisal Prize in Arabic Language and Literature.

Distinguished Achievement in Research Award:

Gregory Afinogenov, Ph.D, Associate Professor, Department of History, College of Arts & Sciences

Professor Gregory Afinogenov is recognized for his prize-winning book, Spies and Scholars: Chinese Secrets and Imperial Russia’ Quest for World Power (Harvard University Press, 2020). The book is the winner of three awards thus far: the 2020 Thomas J. Wilson Memorial Prize bestowed by Harvard University Press on the year’s best first book published with the press; the 2021 W. Bruce Lincoln Prize (awarded for “an author’s first published monograph or scholarly synthesis that is of exceptional merit and lasting significance for the understanding of Russia’s past” by this country’s main professional association of Slavic Studies scholars—the Association for Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies); and the Independent Publisher Book Awards’ 2021 Gold Medal in the category of World History. Afinogenov is likely one of the few people in the world with the breadth and depth of linguistic, cultural, and historical knowledge necessary to have undertaken a multi-archival project on the history of Russo-Chinese relations over the course of the 17th- to-19th centuries. The excitement around Professor Afinogenov’s book is a reflection of its striking interpretive originality.

Sonnenborn Chairs honor collaborative teams of faculty.

Sonneborn Interdisciplinary Collaboration Chair #1:

Lisa Singh, Professor, Computer Science Department, College of Arts & Sciences; McCourt School of Public Policy

Katharine Donato, Professor of International Migration, Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service

Ali Arab, Associate Professor, Mathematics and Statistics Department, College of Arts & Sciences

This collaborative team of a computer scientist, a demographer, and a statistician are developing a conceptual and computational framework to predict forced human migration, one of the world’s pressing problems. The framework accounts for 1) variation in the influences on forced migration across time and space, 2) differences in the influences across initial moves and secondary moves, 3) and differences in the types of forces migration contexts (e.g., war, famine, extreme weather). Using a computationally-driven grounded theory approach, their work examines how different drivers interact at different stages of migration. They combine organic data from Google searches, daily events, and social media platforms with traditional administrative and survey data, to develop computational models that account for the unique spatial-temporal dependencies in various migration situations.

Sonneborn Interdisciplinary Collaboration Chair #2:

Rogaia Abusharaf, Professor of Anthropology, GU-Q

Ananya Chakravarti, Professor, Department of History, College of Arts & Sciences

Cóilín Parsons, Professor, Department of English, College of Arts & Sciences

This collaborative team of an anthropologist, historian, and an English professor has been actively studying the Indian Ocean region, home to nearly half the world’s population. This region has acted as a connective tissue globally through the movement of goods, peoples, religious beliefs, and intellectual ideas. The three chairs have collaborated over almost a decade, blending their specialties together for alternative perspectives on the region. This collaboration has been facilitated by the Indian Ocean Working Group founded at GU-Q in 2014. This collaboration has produced dozens of research products and most recently led to a new academic journal, Monsoon: Journal of the Indian Ocean Rim, with the team collaborating on editorial duties. The team has collaborated on teaching through the Global Classroom and Global Humanities Seminars. The team will extend their collaboration to a new set of students, Indian Ocean Fellows, creating new collaborations between students in DC and Doha, through co-taught seminars. In a real sense, this team will create a interdisciplinary laboratory on the Indian Ocean region.

When you next encounter any of these colleagues, convey our pride in their accomplishments!

Office of the ProvostBox 571014 650 ICC37th and O Streets, N.W., Washington D.C. 20057Phone: (202) 687.6400Fax: (202) 687.5103provost@georgetown.edu

Connect with us via: