The title of this blog has inherent redundancies – the words “global” and “research” might be read as implying there is another option, something that might be called the “nonglobal research university.” Such an institution no longer exists.

Over the past few decades, with special acceleration from the use of the internet, scholars around the world have formed groupings of those with similar intellectual interests. It is very common for a faculty member in a department or unit to have closer ties with a scholar in another country with regard to research interests than with colleagues right down the hallway from their office. The evolution of knowledge has defined deeper and narrower specialties nurturing such global networks.

The above focuses on the research lives of faculty, but global research universities also achieve their impact through education. Both undergraduate and graduate education, when led by faculty at cutting edges of their fields, influences the ways of approaching phenomena in their field. They build “schools of thought.” The students are imprinted with that way of thinking, making the influence of life long value.

The United States has been the beneficiary of a virtuous cycle in this regard. Because of the historical larger levels of research support and a culture supporting creativity and innovation, the country built one of the strongest ecosystems of institutions of higher education. It consists of community colleges, small liberal arts private colleges, state colleges, and large private and state research universities. They collectively have become magnets for the brightest minds in the world. They come to the US to receive formative education; some of them stay to work and contribute to the next generation of knowledge production within the US.

There are some data to document how important is the global attraction of US education. Over the past 15 years for the social and behavioral sciences, natural sciences, and engineering, there is a large growth in numbers of international graduate students in US universities as well as a growth in the percentage of all graduate students in those fields from outside the US. In 2000, about 40% of all graduate students were neither US citizens nor permanent residents; by 2015 the percentage was 50%. The US universities training in the engineering sciences were dominantly non US citizens (69%). (It is notable that the growth trend rather dramatic reversed itself between 2016 and 2017 (see the National Science Board report.)

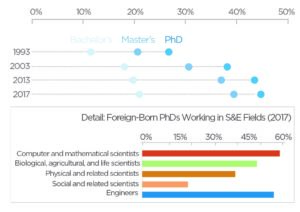

Such numbers affect the workforce of science and engineering which has become increasingly foreign-born as the chart below illustrates

Percentage of All Science and Engineering Workers Who are Foreign-Born

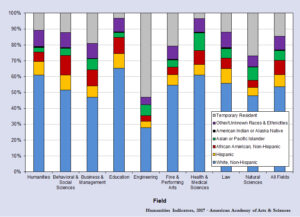

The growing prevalence of international students is not just a phenomenon of the sciences. The stacked bar chart below shows in the top grey sections the percentage of doctoral recipients in 2015 who are temporary residents of the US. One can easily see how engineering, and the natural sciences have much higher percentages of international students. What is also surprising, however, is the percentage of “Fine and performing arts.” Not all international students are coming for science and engineering.

Racial/Ethnic Distribution of 2015 Doctoral Degree Recipients, Selected Academic Fields

That produces, however, a more diverse faculty body. About 6% of US faculty are nonresident aliens. Most of these were also trained in US graduate programs. Many of their foreign-born colleagues have become permanent residents or citizens.

We should lament the falling percentage of US citizens investing in their graduate educations. Our country is leaving behind many talented US students, especially those in economically disadvantaged situations. In the meantime, however, the case is strong that the US profits from the talented young minds who come to our universities for education (with the very best staying here) from around the world.

Any global research university would be greatly diminished if it evolved to a nonglobal university. The United States strength in innovation and creativity has clearly rested on its attractiveness to international students. The country needs them.

Provost Groves, you speak truly. I am one of those foreign-born, US-minted PhDs (Princeton 2004), who chose to stay and I have spent my entire 26 years of teaching in US institutions of higher learning in three different states. I have, I think, been a productive contributor to my (humanities) discipline and to the country I now call home and of which I am a naturalized citizen. Multiply my experience by x many students and colleagues and one can see how the blow to knowledge and to the economy would be significant if we had not come to study here and had not stayed. Is there any data on the percentage of professors that are foreign-born in US institutions of higher ed? Or even at Georgetown? It would be interesting to know this statistic.